ISRAEL’S TITLE UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW TO JUDEA AND SAMARIA (“West Bank”) AND THE GAZA STRIP AND THE LEGALITY OF JEWISH SETTLEMENT IN THESE AREAS (including specific reference to Hebron)

Rabbi Dr. Chaim Simons

revised edition, October 2010

first edition June 2007

INTRODUCTION

The objective of this paper is to determine Israel’s title to and the legality of Jewish settlement on the West Bank(1) , (including specific reference to the city of Hebron, which is situated in the southern part of the West Bank) To this end, the following questions will be discussed:* Under International Law, who has the strongest title to the West Bank?

* What are the requirements of United Nations Resolution 242 for the extent of an Israeli withdrawal from territories captured on the West Bank in 1967?

* Is there a historical basis to support the claims of the entity popularly known as “Palestinian Arabs” having lived in Palestine since antiquity?

* For how long has there been a Jewish settlement in Hebron?

* Is Jewish settlement on the West Bank legal?

THE WEST BANK UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW

A study will now be made in order to determine who today has the strongest title to the West Bank and the Gaza stripPre-1947

The international lawyer Dr. Elihu Lauterpacht has written that in order to determine the title to a particular area “the normal procedure is to trace the chain of title back from the present claimant to a holder whose rights were unquestioned.”(2)

In the case of Palestine, of which the West Bank is part of, Turkey was the unquestioned holder and one need not go further back than the period of Ottoman rule. In July 1923, Turkey signed the Treaty of Lausanne, in which she renounced her rights and title to various territories which included Palestine.(3) By that time(4) the Council of the League of Nations had already granted the Palestine Mandate to Britain.(5) The question of Sovereignty over mandated territories had puzzled international lawyers for decades and there are a number of possibilities as to where the sovereignty rested. These include the League of Nations, the Mandatory Powers, or that the sovereignty was in abeyance.(6) A possible solution to this question came in 1950 when Sir Arnold McNair in his separate opinion on the International Status of South-West Africa stated that “Sovereignty over a Mandated Territory is in abeyance.”(7)

The sovereignty over Palestine when the Mandate over Palestine terminated is discussed by Lauterpacht and he suggested the possibility of a sovereignty gap.(8) In accordance with the opinion of Sir Arnold McNair, this would be a continuation of the Sovereignty vacuum which existed during the life of the League of Nations.

However, since all are agreed that sovereignty was located somewhere or was in abeyance, it has been pointed out by international lawyers that “no mandated territory can be regarded, on the termination of the mandate over it, as a res nullius open to acquisition by the first comer,”(9) and that “sovereignty could only be acquired by lawful action.”(10)

Partition Resolution of 1947

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 181 which called for the partition of Palestine into two states – one Jewish and one Arab.(11) Not only did the Arabs reject this Resolution verbally, they immediately perpetrated acts of terror against Jews in Palestine and in various Arab countries.(12)

When the British left Palestine nearly half a year later on 15 May 1948, this area was immediately invaded by the forces of six Arab states. These Arab states tried to justify their armed intervention but this was not accepted by the Security Council. In the words of Mr. Tarasenko, the delegate of the Ukraine (which was then part of the Soviet Union) “…. an armed struggle is taking place in Palestine as a result of the unlawful invasion by a number of [Arab] States ….”(13)

As a result of the war triggered by this armed invasion of the Arab states, part of the proposed Arab State was captured by Transjordan – namely the area known by the world today as the West Bank and it was annexed in April 1950; part was captured by Egypt – the Gaza Strip; the remainder was captured(14) by Israel.

They all held on to these areas until the Six Day War in June 1967 when they were captured by Israel. During the years following this war, a number of authorities in international law gave their opinions on what had been the legal status of Transjordan and Egypt in the parts of Palestine which had been captured by them in 1948-49.

Dr. Yehuda Blum (Lecturer in International Law at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem): “The use of force by the contiguous Arab States having been illegal, it naturally could not give rise to any valid legal title. Ex injuria jus non oritur.”(15)

Dr. Elihu Lauterpacht (Lecturer in Law at the University of Cambridge): “…Jordan was not entitled to claim any of the areas west of the river Jordan [West Bank] … and Egypt was not entitled to assert sovereignty over the Gaza Strip.”(16)

Alan Levine (New York University Law School): “Since the invasion by Jordan was a violation of international law, it therefore did not give rise to any valid legal title.”(17)

Meir Shamgar (Attorney-General of Israel and later President of the Israel Supreme Court): “… the interpretation most favorable to the Kingdom of Jordan, her legal standing in the West Bank was at most that of a belligerent occupant following an unlawful invasion.”(18)

Dr. Julius Stone (Professor of International Law and Jurisprudence at the University of Sydney): “It [Jordan] was a belligerent occupant there [West Bank].”(19)

The only countries in the world to recognize this annexation of the West Bank by Transjordan were Britain and Pakistan. Even the other Arab countries did not recognize it. In fact when Transjordan performed this annexation, the Political Committee of the Arab League voted to expel her from this League.(20)

Britain, who was one of the two countries who recognized this annexation was inconsistent in this matter. On one hand, Kenneth Younger, the Acting Foreign Secretary, announced to the House of Commons in April 1950, in connection with Transjordan’s annexation of the West Bank, “His Majesty’s Government have decided to accord formal recognition to this union.”(21) On the other hand, Selwyn Lloyd, the Foreign Secretary, said in the House of Commons in March 1957, “The facts about the Gaza strip seem to me to be these. No country has legal sovereignty.”(22) Yet in international law, the West Bank and the Gaza strip had the same status! How then could Britain recognize Transjordan’s annexation of the West Bank?

Legal Status of Israel after the War of Independence

By the end of the War of Independence in 1949, Israel was in possession of the area of Palestine allotted in the Partition Resolution to the Jewish State and parts of the area allotted to the Arab State.

Lauterpacht states that Israel acquired valid title to “those parts allotted to the Jewish State under the Partition Plan, because Israel could not, and did not, commit any infringement of anyone else’s rights in perfecting its title to those parts,” and to “those parts of Palestine outside the area allotted to the Jewish State, which Israeli forces were compelled to occupy by way of self-defensive measures during the fighting of 1948-49.”(23) The latter included West Jerusalem, Beersheba, Ramle, Lod, Nazareth, Acre, Nahariya, Jaffa, Ashdod and Ashkelon.

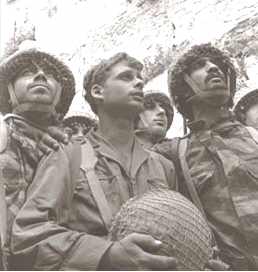

Six Day War

During the weeks preceeding the Six Day War of June 1967, Egypt began to move her troops into the Sinai peninsula, the numbers increasing from day to day. Egypt demanded the total removal of the United Nations Emergency Force from Sinai, to which the United Nations immediately complied. This was immediately followed by Egypt illegally blocading the Straits of Tiran, which was Israel’s sea outlet to the Far East. Syrian troops were poised to strike at the Jordan Valley, whilst the Jordanian mobilised forces had their artillary and mortars directed at Israel’s population centres in Jerusalem and the narrow coastal plain. During those days there were declarations of belligerence by Egypt and the other Arab states, which included stating their intention “to wipe Israel off the map.”(24)

Therefore, in view of the serious danger Israel felt herself in, on 5 June 1967 she made a pre-emptive strike to destroy the air-power of the neighbouring countries. The Israeli cabinet had made this decision on 4 June and this fact was officially publicized five years later by the Israeli Prime Minister, Golda Meir. It stated that “The Government resolves to take military action in order to liberate Israel from the stranglehold of aggression which is progressively being tightened around Israel...”(25)

The use of self-defence by both a country and an individual is a basic human right, and is clearly permitted in both international and domestic law. A question which has been hotly debated is whether pre-emptive strikes are permitted and what is the international law regarding pre-emptive strikes against an enemy country?

According to Article 51 of the United Nations Charter, “Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations...”(26)

International lawyers are divided on the question of whether a country must actually wait for another country to attack before attacking it.

Professor Josef Kunz writes that “the ‘threat of aggression’ does not justify self-defense under Article 51.”(27) In a similar vein Professor Hersch Lauterpacht holds that “a State would be acting in breach of its obligations under the Charter if it were to invade or commit an act of force within the territory of another State, in anticipation of an alleged impending attack...”(28)

On the other hand Professor Julius Stone in an article on this subject (with particular reference to the start of the Six Day War) writes, “The action of the State of Israel on June 5, 1967, even if its forces were to be taken to have crossed the frontier first, would still be within the protection of the reserved right of self-defence under Article 51 .... An ‘armed attack’ may already exist when one side (in this case the Arab States) has deliberately set up a military situation in which the only options given to the opponent are either to defend itself immediately or submit to almost certain destruction.”(29) Similarly Dr. Allan Gerson has said, “... common sense dictates to any observer of state practice that a strict interpretation of article 51 can only lead to creation of a ‘credibility gap’ for the Charter’s provisions. States have demonstrated that they are not prepared to be ‘sitting ducks’ willing to risk sustaining imminent and potentially devastating strikes so that their actions may be justified as ‘lawful’.”(30)

During the period of and immediately after the Six day War, the United Nations General Assembly convened to discuss the situation and draft resolutions were submitted by the Soviet Union and by Albania to condemn Israel for her actions.

The Soviet Union’s resolution included the following:

“Vigorously condemns Israel's aggressive activities and the continuing occupation by Israel of part of the territory of the United Arab Republic, Syria and Jordan, which constitutes an act of recognized aggression; Demands also that Israel should make good in full and within the shortest possible period of time all the damage inflicted by its aggression on the United Arab Republic, Syria and Jordan and on their nationals, and should return to them all seized property and other material assets.”(31)

Albania’s resolution was similarly worded.(32)

Both these draft resolutions were soundly defeated.(33) They did not even receive a simple majority, let alone the two-thirds majority required for acceptance.

On this, Alan Dershowitz, Professor of Criminal Law at Harvard Law School, wrote, “The illegal Egyptian decision to close the Straits of Tiran by military force was recognized by the international community to be an act of war.”(34)

In a similar vein, following a long detailed legal analysis of this situation, Dr. William O’Brien, Director of the Institute of World Polity at Georgetown University, concluded, “I find the Israeli recourse to armed force in anticipatory self-defense reasonable, the more so since the means used combined sound military science with concern for the laws of war by concentrating on military targets.”(35)

Legal status of Israel in the West Bank

Above were quoted the opinions of a number of experts on international law showing that Jordan never had any title to the West Bank nor Egypt to the Gaza Strip. What was the international legal position on this question following the Six Day War when Israel captured these areas? Here are the opinions of a number of authorities on international law:

Dr. Yehuda Blum: “The legal standing of Israel in the territories in question [West Bank] is thus that of a State which is lawfully in control of territory in respect of which no other States can show a better title.”(36)

Dr. Benjamin Halevi (former Judge in Israel Supreme Court) “… it [Israel] has a better title than Egypt over the Gaza Strip and than Jordan over Jerusalem and those territories [West Bank] which are historically part of Palestine…”(37)

Alan Levine: “…[Israel] is in control of territory to which no one can assert a more valid claim.”(38)

Professor Stephen Schwebel (former United States State Department Legal Advisor and later President of the International Court of Justice): “… there is a grave question about the title of any State but Israel to territory which was Palestinian territory in 1948. Vis-à-vis Jordan on the one hand and Egypt on the other, Israel has better title because it was acting lawfully and defensively in 1948 and in 1967….”(39)

Dr. Julius Stone: “She [Israel] is a State in lawful control of territory [West Bank] in respect of which no other State can show a better title.”(40)

One can notice that these authorities use expressions such as “Israel has better title” rather than the term “sovereignty.” Dr. Blum discusses this point and writes, “It must be remembered that title to territory is normally based not on a claim of absolute validity … but rather on one of relative validity…. Since … no State can make out a legal claim that is equal to that of Israel, this relative superiority of Israel may be sufficient, under international law, to make Israel possession of Judea and Samaria [West Bank] virtually indistinguishable from an absolute title, to be valid erga omnes.”(41) (emphasis in original). He brings support for this statement of his from a judgment of the International Court of Justice from 1953, in “The Minquiers and Ecrehos Case” when they were called upon to adjudicate a territorial dispute between Britain and France, where they decided “to appraise the relative strength of the opposing claims to sovereignty over the Ecrehos.”(42)

Legal status of Transjordan

So far it has tacitly been assumed that there is no question regarding the legality of Transjordan. But as it will now be shown, the matter is not at all clear cut.

The aim of the Mandate for Palestine, as stated in its preamble and in Article 2 was to prepare the area for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” There is no mention of the establishment of a national home for the Arabs.

The area known as Palestine in this Mandate document extended from the Mediterranean to the eastern border of what is today known as Jordan. Article 6 of this document stated that an aim of the Mandate was to “encourage, in co-operation with the Jewish agency... close settlement by Jews on the land” – namely on the entire area of Palestine.

However, Article 25 allowed the Mandatory, with the consent of the League of Nations, “to postpone or withhold application” certain articles (which specifically excluded amongst others Article 15) of this Mandate “in the territories lying between the Jordan and the eastern boundary of Palestine” (namely the area subsequently known as Transjordan). This area of Transjordan comprised 76 per cent of the Palestine Mandate. It must however be stressed that Transjordan was always part of the British Mandate over Palestine.

Although this meant that Jewish settlement organised by the Jewish Agency could no longer take place in Transjordan, individual Jewish settlement was not legally excluded. However, in practice Jews were prevented from living in Transjordan(43) which was contrary to Article 15 of the Mandate which states inter alia, “No discrimination of any kind shall be made between the inhabitants of Palestine on the ground of race, religion or language.”

The compatibility with the Mandate of a treaty signed between Britain and Transjordan in 1928 came up at a meeting of the League of Nations in September of that year. In answer, the British delegate, Lord Cushendun, declared that “In Transjordan, however, the Palestine mandate remains in full force.(44)

However despite this, in March 1946, Britain acting unilaterally negotiated the “Treaty of London”(45) with Transjordan and thereby detached the area of Transjordan from the Mandate setting up an “independent sovereign State” named Transjordan. At the final meeting of the League of Nations, held just a few weeks later, the British delegate, Viscount Cecil of Chelwood stated, “The mandates administered by the United Kingdom were originally those for Iraq, Palestine, Transjordan, Tanganyika, part of the Cameroons, and part of Togoland” – thus disingenuously indicating the existence of two separateMandates for Palestine and Transjordan! He then just “notified” the meeting that Transjordan had become an “independent sovereign State … just the other day in 1946.”(46)

This act was contrary to Article 5 of the Mandate which states that “The Mandatory shall be responsible for seeing that no Palestine territory shall be ceded or leased to, or in any way placed under the control of, the Government of any Foreign Power.” On this question, Joseph Nedava, Professor of Political Science at the University of Haifa, wrote, “As the Hashemite Kingdom [of Jordan] rests on an illegal base, its independent status is invalid from its very inception. It ought still to be considered part of what was formerly Palestine.”(47)

THE SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTION OF NOVEMBER 1967

Following extensive debates and consultations between members of the United Nations Security Council, which took place several months after the Six Day War of June 1967, a Resolution proposed and drafted by Britain was finally unanimously approved by them. This Resolution is today well-known as “Security Council Resolution 242.”(48)Paragraph 1(i) of this Resolution states “Withdrawal of Israel armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict.”

There has been much debate by both lawyers and politicians over the meaning of this paragraph. Does it mean all the territories or just some of the territories captured by Israel during the Six Day War. On the face of it, the wording could be ambiguous since it does not state “all the territories” or even “the territories” but just “territories.”

An answer to this can be found from a study of the background to the acceptance of this Resolution and the explanations of those who drafted the wording of it.

Background to acceptance of Resolution

Before this Resolution was approved, there were a number of different drafts submitted by various members of the Security Council. The Soviet Union’s draft Resolution included:

“The parties to the conflict should immediately withdraw their forces to the positions they held before 5 June 1967….”(49) – namely an Israeli withdrawal from all territories captured during this war. In addition, the delegate of the Soviet Union, Mr. Kuzenetsov, stated during his speech to this Council, “Our draft resolution contains a clear clause on the key question, namely the withdrawal of Israel troops from all occupied territories of the Arab States to the positions that they held prior to 5 June 1967.”(50) However, this draft resolution was never approved by the Security Council.

Several months prior to the Security Council considering draft resolutions on this conflict, the United Nations General Assembly extensively debated the question and several draft resolutions were submitted which also included the question of Israeli withdrawal.

One of these was by the Soviet Union and this included:

“Demands that Israel should immediately and unconditionally withdraw all its forces from the territory of those States to positions behind the armistice demarcation lines.”(51) A similar wording was included in draft resolutions submitted by Albania,(52) by a host of Central and South American countries,(53) and by a host of African and Asian countries.(54) All these four draft resolutions, which demanded a total withdrawal by Israel, were defeated when voted upon.(55)

Explanations from those drafting Resolution

Resolution 242 was drafted by the British Government (with some Unites States assistance) and in the following years the interpretation of the words “withdrawal from territories” was explained on many occasions by those involved in drafting it. Here are some examples:

In November 1969, Michael Stewart, the British Foreign Secretary was asked the following question in the British Parliament, “What is the British interpretation of the wording of the 1967 Resolution? Does the right hon. Gentleman understand it to mean that the Israelis should withdraw from all territories taken in the late war?” His reply was, “No, Sir. That is not the phrase used in the Resolution. The Resolution speaks of secure and recognized boundaries. These words must be read concurrently with the statement on withdrawal.”(56)

George Brown, who had been British Foreign Secretary, commented in January 1970 at the end of his visit to Israel, “I have been asked over and over again to clarify, modify or improve the wording, but I do not intend to do that. The phrasing of the resolution was very carefully worked out, and it was a difficult and complicated exercise to get it accepted by the U.N. Security Council.”(57) A few days earlier in a meeting with Arab leaders, his words on this subject were even clearer, “I formulated the Security Council resolution. Before we submitted it to the Council, we showed it to Arab leaders. The proposal said ‘Israel will withdraw from territories that were occupied,’ and not from ‘the’ territories, which means that Israel will not withdraw from all the territories. All the leaders of the Arab countries agreed with this text.”(58)

Lord Caradon, who was the British Ambassador to the United Nations when this Resolution was passed and was actively involved in its formulation, told Beirut’s English language newspaper “The Daily Star” on 12 June 1974, “It would have been wrong to demand that Israel return to its positions of June 4, 1967, because those positions were undesirable and artificial. After all, they were just the places where the soldiers of each side happened to be on the day the fighting stopped in 1948. They were just armistice lines. That’s why we didn’t demand that the Israelis return to them.”(59)

Another key draftee of this Resolution was Arthur Goldberg who was the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. He explained that, “The notable omissions in language used to refer to withdrawal are the words the, all, and the June 5, 1967, lines…. In other words, there is lacking a declaration requiring Israel to withdraw from the (or all the) territories occupied by it on and after June 5, 1967. Instead, the resolution stipulates withdrawal from occupied territories without defining the extent of withdrawal. And it can be inferred from the incorporation of the words secure and recognized boundaries that the territorial adjustments to be made by the parties in their peace settlements could encompass less than a complete withdrawal of Israeli forces from occupied territories.”(60) (emphasis in original)

Translation of Resolution into other languages

Resolution 242 was drafted in English and it was the English text which was voted on and unanimously approved. Furthermore, “the negotiations between the members of the Security Council, and with the other interested parties, which preceded the adoption of that resolution, were conducted on the basis of English texts ….”(61)

In the United Nations, at that period, English and French were the working languages and in addition, Russian, Chinese and Spanish were the official languages. Material was translated into these languages and as can sometimes happen, changes in meaning can occur during such translation.

This indeed happened in translating this resolution into French. The crucial sentence “Withdrawal of Israel armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict” when translated into French became “Retrait des forces armees israeliennes des territoires occupes lors du recent conflit.”(62) The difference is that the English text says “territories” whereas the French says “des territoires” which could be translated back into English as “the territories.”

There has been much discussion on this point in the French version and Shabtai Rosenne, who was Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations Office at Geneva wrote, “Many experts in the French language, including academics with no political axe to grind, have advised that the French translation is an accurate and idiomatic rendering of the original English text, and possibly even the only acceptable rendering into French. As an independent scholar of the law has recently written, ‘the expression ‘des territoires’ in [the French] translation may be viewed merely as an idiomatic rendering into French not intended to depart … from the English…’.”(63)

The “Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting in America - CAMERA” also commented on the French text of resolution 242, “Some commentators have argued that since the French ‘version’ of 242 does contain the phrase ‘the territories,’ the resolution does in fact require total Israeli withdrawal. This is incorrect – the practice in the U.N. is that the binding version of any resolution is the one voted upon, which is always in the language of the introducing party. In the case of 242 that party was Great Britain, thus the binding version of 242 is in English. The French translation is irrelevant.”(64)

On a judicial level, the question arising from mistranslations of documents may be found in an Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice in 1955 in the “South-West Africa Voting Procedure” case. In their Advisory Opinion they stated, “In the question submitted to the Court there is a slight difference between the wording of the English and the French texts. The French version seems to express more precisely the intention of the General Assembly ….”(65) Using this principle of “intention of the General Assembly,” Rosenne stated that when applied to our case we can see that prior to the adoption of 242 there were many debates in both the General Assembly and the Security Council and the many draft resolutions put forward in both these bodies demanding a total Israeli withdrawal were defeated or withdrawn.(66)

Furthermore, Ambassador Arthur Lall who had been Deputy Permanent Representative of India to the United Nations, wrote that the sponsors of 242 had resisted all attempts to insert words such as “all” or “the” in the text of this phrase in the English text of this resolution.(67) In fact when the Spanish translation was made, the word “all” crept in but that it was subsequently removed clearly showing that the Israeli withdrawal was not intended to be to the pre-Six Day War lines.(68)

Secure and Recognized Boundaries

Paragraph 1(ii) of Resolution 242 states:

“Termination of all claims or states of belligerency and respect for and acknowledgement of the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of every State in the area and their right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force.”

The meaning of “secure and recognized boundaries” will now be analysed.

Even a mere cursory glance at Israel’s pre-Six Day War boundaries shows how vulnerable they were to enemy attack. The north of Israel was linked to the south by a narrow corridor, which at one point was only 15 kilometers wide. A large percentage of Israel’s population lived in this narrow corridor. Israel’s capital, (West) Jerusalem which also had a large population, was situated at the end of a corridor surrounded on three sides by an enemy state.(69) It would not have been difficult militarily for a properly trained and armed enemy to cut Israel in half and to cut off Jerusalem.

Abba Eban, who was Israel’s Foreign Minister gave an interview to the German newspaper “Der Spiegel”, which appeared in their edition of 27 January 1969. Even though Eban was a strong supporter of giving away territories captured in the Six Day War in exchange for peace, he stated in this interview, “We have openly said that the map will never be the same as on June 4, 1967. For us, this is a matter of security and of principles. The June map is for us equivalent to insecurity and danger. I do not exaggerate when I say that it has for us something of a memory of Auschwitz . We shudder to think of what would have awaited us in the circumstances of June 1967, if we had been defeated; with Syrians on the mountain and we in the valley, with the Jordanian army in sight of the sea, with the Egyptians who hold our throat in their hands in Gaza. This is a situation which will never be repeated in history.”(70)

A more professional assessment of what are secure borders was made by the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff, a few weeks after the Six Day War. The U.S, Secretary of Defense had asked Earle Wheeler who was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff their views “without regard to political factors, on the minimum territory, in addition to that held on 4 June 1967, Israel might be justified in retaining in order to permit a more effective defense against possible conventional Arab attack and terrorist raids.”

On 29 June 1967, they presented the Secretary of Defense with their answer. Included with their secret Memorandum was a map of the region with shaded areas designating in their own words “Minimum territory needed by Israel for defensive purposes.” This shaded area includes the area around Sharm ash-Shaykh at the southern tip of the Sinai peninsula, the entire Gaza strip, the Golan heights and the majority of the West Bank. From a little below Jerusalem southwards, this minimum area extends all the way to the Dead Sea.(71)

One might mention that this memorandum only came to light after the “Wall Street Journal” published an article about it in March 1983.(72)

The question of recognized boundaries will now be discussed. The 1947 Partition Plan of the United Nations gave boundaries for the then proposed Jewish and Arab states. As the result of the Arab attack on the emerging Jewish state in May 1948, a war followed and during it Israel captured a sizeable part of the area designated for the proposed Arab state. This war ended with Armistice agreements being signed with the four neighbouring Arab states. Reference to “demarcation lines” between Israel and its neighbours were included in these agreements.

With Egypt this fact is clearly stated: Article V paragraph 2: “The Armistice Demarcation Line is not to be construed in any sense as a political or territorial boundary, and is delineated without prejudice to rights, claims and positions of either Party to the Armistice as regards ultimate settlement of the Palestine question.”(73)

In the case of Jordan, the wording is not so direct: Article II paragraph 2: “It is also recognized that no provision of this Agreement shall in any way prejudice the rights, claims and positions of either Party hereto in the ultimate peaceful settlement of the Palestine question, the provisions of this Agreement being dictated exclusively by military considerations. Article IV paragraph 1: “The lines described in articles V and VI of this Agreement shall be designated as the Armistice Demarcation Lines and are delineated in pursuance of the purpose and intent of the resolution of the Security Council of 16 November 1948.” Article IV paragraph 2: “The basic purpose of the Armistice Demarcation Lines is to delineate the lines beyond which the armed forces of the respective Parties shall not move.”(74) Article VI paragraph 9: “The Armistice Demarcation Lines defined in articles V and VI of this Agreement are agreed upon by the Parties without prejudice to future territorial settlements or boundary lines or to claims of either Party relating thereto.”

In addition, similar wording as found in the Egyptian Armistice agreement was stated in a meeting of the Security Council by Muhammed El-Farra, the Permanent Representative of Jordan to the United Nations, on 31 May 1967 – less than a week before the Six Day War. The day before, Jordan and Egypt had signed a mutual defense pact solidifying the Arab front, and Jordan was thus confident that the Arab states would imminently destroy Israel. At this meeting Jordan’s representative stated, “There is an Armistice Agreement. The Agreement did not fix boundaries; it fixed a demarcation line. The Agreement did not pass judgment on rights-political, military or otherwise. Thus I know of no territory; I know of no boundary; I know of a situation frozen by an Armistice Agreement.”(75)

It can thus be seen that when the Six Day War started Israel had neither secure nor recognized borders and Resolution 242 did not call for the withdrawal of Israeli forces to the pre-Six Day War lines but only to “secure and recognized boundaries.”

THE ORIGIN OF THE TERM “PALESTINIAN ARABS”

Today, the Arabs and much of the world claim that an entity known as the “Palestinian Arabs” has existed in Palestine since time immemorial. Whether or not there is a factual basis to this claim will now be investigated.It is very reasonable to expect that had such an entity already existed by the first quarter of the 20th century, it would appear in documents written during that period. However, a study of such documents shows it to be completely absent. Here are some examples:

Balfour Declaration(76) : This document dated 2 November 1917, speaksonly of “the establishment in Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish people.” The non-Jewish population are not even referred to as Arabs and the only rights they were envisaged to have were “civil and religious” – namely, there is no mention for them of any political rights.

Political rights were indeed guaranteed to the Arabs in other Middle East Mandates – namely in the Mandate for Syria and Lebanon and in the draft Mandate for Mesopotamia (Iraq). Article 1 of the “French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon”(77) states inter alia, “This organic law shall be framed in agreement with the native authorities and shall take into account the rights, interests, and wishes of all the population inhabiting the said territory. The Mandatory shall further enact measures to facilitate the progressive development of Syria and the Lebanon as independent States.”(78) The draft Mandate for Mesopotamia (Iraq) had these identical provisions.(79) In addition, the Arabs received from Britain 76 per cent of the area of the Palestine Mandate (namely Transjordan) under questionable circumstances.

British Mandate for Palestine: The agreed text was confirmed by the Council of the League of Nations on 24 July 1922. This document has a Preamble and twenty eight Articles. Article 2 begins, “The Mandatory shall be responsible for placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of a Jewish national home.” In the entire document there is no mention of an “Arab National Home.” Indeed the word “Arabs” does not even appear in the entire document. The Peel Report of 1937 thus comments, “Unquestionably, however, the primary purpose of the Mandate, as expressed in its preamble and its articles, is to promote the establishment of the Jewish National Home …[the Mandate] provide[s] for the recognition of a Jewish Agency …. No such body is envisaged for dealing with Arab interests.”(80) (emphasis in original)

Furthermore in the Preamble of this Mandate is written, “Whereas recognition has thereby been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country.” Even though Jews had been driven out of Palestine after the Roman conquest 1800 years earlier, despite the immense difficulties, there was almost always a Jewish presence there.(81) Throughout all the generations the return to Eretz Israel (Palestine) was mentioned in a Jew’s daily prayers(82) and he faced Jerusalem when praying.(83) – (Moslems face Mecca when praying.)

In contrast, there is no mention in the Mandate of any Arab historical connection with Palestine, let alone a “Palestinian Arab” connection. It is true that Arabs had for centuries lived there but as the Peel Report stated. “The Arabs had lived in it for centuries, but they had long ceased to rule it, [Arab rule had been a thousand or so years earlier] and in view of its peculiar character they could not now claim to possess it in the same way as they could claim possession of Syria or Iraq.”(84)

Likewise, the following documents don’t mention “Palestinian Arabs”:

Feisal-Weizmann agreement of 3 January 1919 (85) - Jewish-Arab agreement regarding Palestine.

Feisal-Frankfurter correspondence of early March 1919 (86) - exchange of correspondence between Jew and Arab regarding Palestine.

Recommendations of the King-Crane Commission dated 28 August 1919 (87) - a Commission appointed by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson mainly to determine which of the Western nations should act as the Mandatory power for Palestine.

In 1970 Professor Stone wrote, “The idea of a “Palestinian Entity” is a creature of the decade just passed…. The ‘Palestinian Entity’ notion was invoked by Arab States at Arab League meetings in 1959, in the context of struggles not only against Israel, but also among themselves looking to a still projected dismemberment of that State.”(88)

The non-homogeneous character of the Arabs living in Palestine and their different places of origin are described in “The Handbook for Palestine” of 1930, published by the British Government. Here are some brief extracts: “The Arab population falls naturally into two categories, the nomads (bedawi) and the settled Arabs (hadari). The former are the purer in blood, being the direct descendants of the half-savage nomadic tribes who from time immemorial have inhabited the Arabian peninsula… There is little or no cohesion between the various tribes… A negroid element is found among the inhabitants of the tropical Ghor region in the lower Jordan Valley and around the Dead Sea. The presence of these people is attributed by some to a settlement from the Sudan, by others to the introduction of negro slaves purchased at Mecca by pilgrims and retailed at Ma’an…. The settled Arabs are of more mixed descent than the Beduin… The Aramaic language, after holding its ground for a considerable time in Palestine and Syria, ultimately gave place to Arabic … and this process was facilitated by the continuous replenishment of Palestine and Syria from the tribes of the Arabian Desert. This Arab infiltration has created and maintains the specific racial character of the population.”(89)

The “Esco Foundation for Palestine” in a report dated 1947, gives many of the above facts and in addition states, “The effendi landowners and city Arabs generally are products of the successive waves of conquerors …. In the Gaza district on the southern shore of Palestine, the population is largely of Egyptian origin…. There are also descendants of Moroccan, Tunisian and Algerian emigrants and mercenaries who have brought an admixture of Berber stock.It is highly improbable that any but a small part of the present Arab population is descended from the ancient inhabitants of the land.” (emphasis added). (90)

There is no doubt that there have been Arabs, as distinct from a specific “Palestinian Arab” entity, almost all of whom arrived in Palestine from different parts of the Middle East from the seventh century onwards (about 26 centuriesafter Jews started living there!), just as in the same way as there were Jews living in Iraq, Yemen, North Africa and other parts of this region for at least a similar period of time.(91)

A year prior to the “Esco Report,” Dr. Philip Hitti, Professor of Semitic Literature at Princeton University, and as a representative of the Institute of Arab-American Affairs told the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry, “Sir, there is no such thing as Palestine in history, absolutely not.”(92) To the same Committee, Dr. John Hazam, Professor of History at the College of the City of New York, and also as a representative of this Institute, stated, “Before 1937, when Balfour made his declaration, there was never any Palestine question, or even any Palestine as a political or geographical entity, as Professor Hitti has explained.”(93)

This was again admitted by Zoehair Mohsen, head of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Military Operations Department, in an interview he gave to the Dutch newspaper Trouw in March 1977. After stating that there were no differences between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese, he continued “We are one people. Only for political reasons do we carefully underline our Palestinian identity. For it is of national interest for the Arabs to encourage the existence of the Palestinians against Zionism. Yes, the existence of a separate Palestinian identity is there only for tactical reasons. The establishment of a Palestinian State is a new expedient to continue the fight against Israel and for Arab unity.”(94)

In a similar vein Joseph Farah, an Arab-American who had been a journalist for more than 20 years wrote in May 2001, “There is no distinct Palestinian culture or language. Further, there has never been a Palestinian state governed by Palestinians in history, nor was there ever a Palestinian national movement until after the 1967 Six Day War, when Israel seized Judea and Samaria.”(95)

One might well ask how has this claim by the Arabs of a “Palestinian Arab” entity been accepted as fact by the rest of the world. This is a result of extensive propaganda by the Arab world, who have almost unlimited money as result of their oil revenues. One only has to look at Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union to see the power of propaganda. An example of Arab propaganda in this field is a 12 page paid advertisement in the British daily newspaper “The Guardian” in May 1976 entitled the “Palestine Report” which even created sections on Palestinian embroidery and cookery!(96)

In conclusion, one might add that the name “Palestine” is not a name given to the area by the Arabs. In fact the name “Palestine” was originally an adjective derived from the Hebrew word “peleshet” and it was first mentioned by Herodotus (many hundreds of years before there were Arabs in the area) in the form of “the Palestine Syria.”(97)

THE JEWISH PRESENCE IN HEBRON THROUGHOUT THE AGES

From Biblical Times, Jews have lived in Hebron.(98) The Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob had their home there. Abraham purchased the Cave of Machpelah and there the three Patriarchs and three of the Matriarchs were buried. The city and its environs were conquered at the time of Joshua by Caleb. King David ruled 7 years in Hebron before he continued his rule in Jerusalem.Hebron was incorporated into the (Jewish) Hasmonean kingdom by John Hyrcanus and King Herod built a 12 metre high wall (still standing today) over the Cave of Machpelah. Jews continued living in Hebron after the Bar Kochba Revolt in the year 135, and during the Byzantine period. The remains of a Synagogue from the Byzantine period have been excavated.

Jewish settlement continued there after the city was conquered by the Arabs in the year 638, until the Crusaders captured it in 1100 and expelled the Jewish community, (although there is evidence that Jews remained there during part of the period of the Crusaders – this fact was discovered in a document found in the Cairo Geniza, which refers to a Jewish Community near the Cave of Machpelah during the 11th and 12th centuries;(99) the 12th century was already the period of the Crusaders, so at least during part of Crusader rule in Palestine, a Hebron Jewish community existed.) The Jewish community was re-established following the Mameluke conquest of Hebron in 1260.

Following the Ottoman conquest of Hebron in 1517 there was a lapse in Jewish settlement of up to 15 years. About 1540, Jews from Spain purchased the site now known as the “Abraham Avinu” courtyard and built a Synagogue by that name there. During the 400 years of Ottoman rule the Jewish community of Hebron grew in size and purchased further land. Many Synagogues, Yeshivas (Rabbinical Colleges), Talmud Torahs (Jewish Religious Schools), a Jewish hospital and clinic, and Gemachim (free loan societies) were established. Here are a few examples:

In 1807, the Jewish community, despite its poverty, purchased a 5 dunam site situated in front of the “Abraham Avinu” courtyard, a sale which was recognized by the Hebron Wakf. At the beginning of the 19th century, Lubavitch (Habad) Hassidim settled in Hebron and built a Synagogue next to the Abraham Avinu Synagogue.

In 1879, a wealthy Turkish Jew, Haim Yisrael Romano purchased a plot of land and on it built a building known as Beit Romano. About 30 years later the Rebbe of Lubavitch bought this building together with the surrounding area and established a Yeshiva there.(100) In 1893, a building, later known as Beit Hadassah, was built by the Hebron Jewish community and this later became the Jewish clinic. In 1925, Rabbi Mordechai Epstein established the Slabodka Yeshiva in Hebron.

During the period of Ottoman rule, a number of prominent Rabbis lived in Hebron and on their death were buried in the Jewish cemetery, for which in 1811, an additional 800 dunams of land had been purchased. Amongst those buried there are Rabbi Hizkiyahu Medini (author of “Sedei Hemed”), Rabbi Eliyahu De-Vidash (author of “Reishit Hochma”), Rabbi Eliyahu Mani and Rabbanit Menucha Rachel Slonim.(101)

The year 1929 was the year of the infamous Hebron pogrom in which 67 Jews were brutally massacred by the Arabs and many others permanently injured.(102) The surviving Jews went to live in Jerusalem. In 1931, some Jewish families returned but in 1936 following the Arab uprising, the British authorities moved them out.

Following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and the subsequent Arab invasion, Hebron was captured by Transjordan and annexed to that country. The Abraham Avinu Synagogue was destroyed by the Jordanians and they then converted the site into a sheep pen. The Jewish cemetery was likewise destroyed by them and it was ploughed over and tomatoes, vines and fig trees planted over the site and a latrine built there.(103)

For a period of about 700 years ending with the Six Day War in 1967, Jews were barred by the Moslems from entering the Cave of Machpelah and could only ascend to the seventh step outside the eastern wall. A publicised incident from 1935 shows it was strictly enforced. That year, the Gerrer Rebbe, who was one of the greatest Rabbis of his generation, went above this seventh step and as a result the Arabs started screaming and even violence followed.(104)

THE LEGALITY OF JEWISH SETTLEMENT ON THE WEST BANK, WITH PARTICULAR REFERNCE TO HEBRON

During the 43 years since the Six Day War, over 300,000 Jews have settled on the West Bank(105) (excluding East Jerusalem). There has been considerable debate whether under international law these settlements are legal.Those opposing settlement base their objections using the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949.(106) However, the first question to resolve is whether this Convention applies today to the West Bank. Article 2 paragraph 2 states: “The Convention shall also apply to all cases of partial or total occupation of the territory of a High Contracting Party…” (emphasis added). Jordan is a High Contracting Party to this Convention but, as shown above, her status in the West Bank was that of a belligerent occupant, and in addition this area does not belong to any other State, and so the Convention does not apply to Israel in the West Bank. After stating this point, Professor Stone comments “This is a technical, though rather decisive, legal point.”(107)

However, in July 1999, a Conference of “High Contracting Parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention” held in Geneva “reaffirmed the applicability of the Fourth Geneva Convention to the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem,”(108) and this was “reaffirmed” in December of that year by the United Nations General Assembly.(109) In fact, it is very difficult to understand this “reaffirming” judicially, and it clearly seems to have strong political overtones!(110) This is especially so since only two countries in the entire world recognized Jordan’s annexation of the West Bank.

One might also state that in the War of Independence of 1948-49, Israel captured areas of Palestine (which included Beersheba, Jaffa, Lod, Ashkelon) which were situated beyond the Partition borders of United Nations Resolution 181, and many Jews have settled in these places. Those claiming that settlements on the West Bank contravene the Fourth Geneva Convention should likewise claim this for Jewish settlement in the areas captured in the War of Independence – but they have not done so! It is relevant to mention that Professor Quincy Wright equates territory captured in the Six Day War with that captured in the War of Independence.(111)

Even, if one accepts just for the sake of argument, that this Convention does apply to Israel in the West Bank, is Jewish settlement in this area in contravention of this Convention? Those claiming that it does, bring Article 49 paragraph 6 in support of their contention. This paragraph states: “The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.”

There is an official commentary to this Convention written by the International Committee of the Red Cross.(112) On this paragraph they write that it was included in order “to prevent a practice adopted during the Second World War by certain Powers, which transferred portions of their own population to occupied territory for political and racial reasons or in order, as they claimed, to colonize those territories. Such transfers worsened the economic situation of the native population and endangered their separate existence as a race.”(113)

These “certain Powers” were mainly Germany and the Soviet Union, and for their “political and racial reasons” would transfer mainly Jews to countries they had “occupied” during the Second World War, for the purpose of extermination and slave-labour. This does not even bear the remotest similarity with the settlement of Jews on the West Bank?

Since this paper includes specific reference to Hebron, this question will mainly be studied in connection with Jewish settlement in Hebron.

The Government of Israel has never transferred or deported any Jews to Hebron. On the contrary, Jews have often had to move to Hebron by stealth. The first group to move permanently to Hebron was under the leadership of Rabbi Moshe Levinger and they booked an Arab hotel, the Park Hotel in Hebron, for the Passover Festival [April] 1968. When they announced their intention to remain, the Government of Israel was politically unable to remove them.(114) In April 1979, a group of women and children in the middle of the night entered the Jewish owned Beit Hadassah building in the centre of Hebron and took up residence. The Government of Israel which was then a right-wing government under the premiership of Menachem Begin, first tried to put a siege on these women and children so that they would leave. However when that failed, they had to accept the fait accompli.(115)

In 2004, the International Court of Justice gave an Advisory Opinion (a non-binding legal interpretation) on the separation fence being built by Israel on the West Bank. In the course of this Advisory Opinion they wrote, “This provision [Article 49(6) of the Convention] prohibits not only deportations and forced transfers such as those carried out during the Second World War, but also any measures taken by an occupying Power in order to organize or encourage transfers of parts of its own population into the occupied territory.”(116) However, the wording of paragraph 6 states that “the Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population….” (emphasis added). Thus even if one were to accept this greatly expanded interpretation of Article 49(6) in this Advisory Opinion, (and in addition accept that this Convention applies to Jews settling on the West Bank), it would be the Israeli Governmentor the Israeli army who would be forbidden to “organize or encourage” the transfer Jews to Hebron, but as has already been stated, Jewish settlers came by stealth. Some of these Jewish settlers managed to remain permanently despite Israeli government opposition, others were evicted by the Israeli authorities,(117) whilst yet other settlers are in the course of litigation with the Israeli authorities concerning their settlement.

The purpose of this Jewish settlement in the heart of Hebron was to re-establish the Jewish presence in Hebron which had existed for over three thousand years until it was effectively terminated in 1929 when the Arabs of Hebron brutally massacred 67 Jews. All Jewish settlement in Hebron till this day has only been in Jewish owned property and property which had been legally purchased from the Arab owners.

The Red Cross commentary on this paragraph of the Convention states “Such transfers worsened the economic situation of the native population and endangered their separate existence as a race.” This will now be looked at in connection with Jewish settlement in Hebron.

The “economic situation of the native population” – in this case, the Arabs of Hebron – has improved as the result of Jews living in Hebron and in the neighbouring Kiryat Arba. Arab labour is cheaper than Jewish labour and often Jews in the area will employ Arabs to do work such as building and carpentry. In the industrial zone of Kiryat Arba, many Arabs have found their employment. Subject to the security of both the Arab and Jewish populations, (which is made worse as the result of Arab terrorist actions, such actions being contrary to the International laws of the conduct of war and in addition being directed against non-combatants), the Arabs of Hebron can live their lives normally. There are numerous Mosques in Hebron where they can pray five times a day in accordance with Moslem practice. The muezzins are free to call the Moslems to prayer through the loudspeakers in the Mosques during all hours of the day and night. One can hardly call the presence of even a thousand Jews in Hebron amongst 150,000 Arabs as endangering the Arabs “separate existence as a race.” [One could add that apart from Jewish settlement in Hebron, all other Jewish settlements on the West Bank are in areas away from Arab concentrations of population.]

A different approach which shows that Jewish settlement in the West Bank is completely legal was put forward by Professor Eugene Rostow, a former U.S. Under Secretary of State and Professor of Law at Yale University. In an article published in the journal “Foreign Affairs” in 1980, Professor Rostow wrote, “The decisions of the Security Council and the International Court of Justice with regard to Namibia, formerly known as German Southwest Africa, make it clear that League [of Nations] Mandates survive as trusts even when Mandatory powers resign or are dismissed, or the Mandatory administration as such is terminated. Since the Palestine Mandate conferred the right to settle in the West Bank on the Jews, that right has not been extinguished, and, under Article 80 of the [United Nations] Charter cannot be extinguished unilaterally.”(118)

Professor Rostow’s statement will now be studied in more detail:

South Africa had following the First World War been given a Mandate for Namibia and in 1970, the Security Council passed a Resolution asking for an Advisory Opinion from the International Court of Justice regarding South Africa’s continued presence in Namibia.(119)

The International Court of Justice looked into the question and in their official “Summary of the Advisory Opinion” wrote, “The mandatory was to observe a number of obligations, and the Council of the League [of Nations] was to see that they were fulfilled. The rights of the mandatory as such had their foundation in those obligations. When the League of Nations was dissolved, the raison d'etre and original object of these obligations remained. Since their fulfilment did not depend on the existence of the League, they could not be brought to an end merely because the supervisory organ had ceased to exist. The Members of the League had not declared, or accepted even by implication, that the mandates would be cancelled or lapse with the dissolution of the League. The last resolution of the League Assembly and Article 80, paragraph 1, of the United Nations Charter maintained the obligations of mandatories. The International Court of Justice has consistently recognized that the Mandate survived the demise of the League…”(120)

. The question which immediately comes to mind is whether the provisions of the “Mandate for Palestine” nearly 60 years after the establishment of the State of Israel are still in force! On this point Professor Rostow answers in the affirmative and elaborates in a later paper of his:

“Many believe that the Palestine Mandate was somehow terminated in 1947, when the British Government resigned as the mandatory power. This is incorrect. A trust never terminates when a trustee dies, resigns, embezzles the trust property, or is dismissed. The authority responsible for the trust appoints a new trustee, or otherwise arranges for the fulfillment of its purpose…. In Palestine the British Mandate ceased to be operative as to the territories of Israel and Jordan when those states were created and recognized by the international community. But its rules apply still to the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, which have not yet been allocated either to Israel or to Jordan or become an independent state. Jordan attempted to annex the West Bank in 1951 but that annexation was never generally recognized, even by the Arab states, and now Jordan has abandoned all its claims to the territory.”(121) (emphasis added)

This right of Jewish settlement all over Palestine is clearly stated in Article 6 of the Mandate for Palestine: “The Administration of Palestine … shall facilitate Jewish immigration under suitable conditions and shall encourage, in co-operation with the Jewish agency …. , close settlement by Jews on the land, including State lands and waste lands not required for public purposes.”

It thus follows that to this very day, Jews have every right to settle, even if organised by the Israeli Government, in all parts of Palestine between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River. This would apply even if the State of Israel were to be illegally occupying the West Bank.

There is another argument which is more general and applies to not only Jews and to not only Palestine and therefore it will just be mentioned here very briefly. This is the specifically preventing of a particular group from settling in a particular place. According to Article 3 of the “International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination” which came into force in January 1969, “States Parties particularly condemn racial segregation and apartheid and undertake to prevent, prohibit and eradicate all practices of this nature in territories under their jurisdiction.”(122)

CONCLUSIONS

1. According to authorities in international law, Israel has a greater right to Judea and Samaria (“West Bank”) and the Gaza Strip than anyone else in the world.2. Resolution 242 of the United Nations Security Council only requires Israel to withdraw to “secure and recognized borders.” According to the U.S. military experts, such borders include most of the West Bank.

3. A “Palestinian Arab” entity is of recent origin.

4. Jews have lived in Hebron almost continuously since the era of the Biblical Patriarchs.

5. Jews have every right in international law to live in the entire West Bank and Gaza. This would also apply even if Israel was a belligerent occupant in these areas, and even if Resolution 242 had demanded atotal withdrawal of Israel, and even if a “Palestinian Arab” entity had lived there since antiquity.

REFERENCES

(1) Throughout this paper the term “West Bank” is used for the area Judea and Samaria, since the term “West Bank” is how it is generally known as throughout the world; likewise the term “Palestine” is used for Eretz Yisrael, since this is the term used in most of the documents and material quoted.(2) Elihu Lauterpacht, Jerusalem and the Holy Places, (London: The Anglo-Israel Association, 1988), p.38

(3) Lausanne Treaty, signed between British Empire, France et al. on one side and Turkey on the other, on 24 July 1923, Article 16. The text may be found in The Treaties of Peace 1919-1923 vol.2, (New York: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1924), pp.959ff.

(4) The Palestine Mandate was signed in London on 24 July 1922.

(5) British Mandate for Palestine, League of Nations, Official Journal, 3rd year, no.8, August 1922, Annex 391, pp.1007-12.

(6) Yehuda Blum, “The Missing Reversioner…,” Israel Law Review, vol.3, no.2, April 1968, p.282; Alan Levine, “The Status of Sovereignty in East Jerusalem and the West Bank,” New York University Journal of International Law & Politics, vol.5, no.3, Winter 1972, p.489.

(7) International Court of Justice, Reports of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders, 1950, International Status of South-West Africa, Advisory Opinion of July 11th, 1950, Separate Opinion by Sir Arnold McNair, p.150.

(8) Lauterpact, op. cit., pp.40-41.

(9) Blum, op. cit., p.283.

(10) Lauterpacht, op .cit., p.42.

(11) United Nations, Official Records of the Second Session of the General Assembly, Resolutions. XVII, Resolution adopted on the Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestinian Question, Resolution 181, 29 November 1947, Future government of Palestine, pp.131-50.

(12) Yigal Lossin, Pillar of Fire (Amud Haesh), trans. Zvi Ofer, (Jerusalem: Shikmona Publishing Company, 1983), pp.495-97.

(13) United Nations, Security Council, Official Records, Third year no.75, 306th Meeting, 27 May 1948, p.7.

(14) According to their political or ideological orientation, writers will use terms such as captured, conquered, liberated, occupied, to describe areas taken by Israel in her various wars with the Arabs. Since this is a legal paper, the neutral term “captured” will be used.

(15) Blum, op. cit., p.283.

(16) Lauterpacht, op. cit., p.44.

(17) Levine, op.cit., p.492.

(18) Meir Shamgar, “The Observance of International Law in the Administered Territories,” Israel Yearbook on Human Rights, vol.1, 1971, (Tel-Aviv University), p.265.

(19) Julius Stone, The Middle East Under Cease-Fire, (Sydney: A Bridge Publication, 1967), p.12.

(20) Whiteman’s Digest of International Law, vol.2, pp.1166-67.

(21) Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, vol.474, 27 April 1950, col.1137.

(22) Ibid., vol.566, 14 March 1957, col.1320.

(23) Lauterpacht, op. cit., p.46.

(24) e.g. Abba Eban’s speech at the United Nations on 19 June 1967, United Nations, Official Records of the General Assembly, Fifth Emergency Special Session, Plenary Meetings, Verbatim Records of Meetings, 1526th Plenary Meeting, 19 June 1967, pp.7-16; Alan Dershowitz, The Case for Israel, (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley, 2003), pp.91-93.

(25) “Meir reveals text of war decision”, Jerusalem Post, 5 June 1972, p.1.

(26) Bruno Simma, ed., The Charter of the United Nations, A Commentary, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), p.661.

(27) Josef Kunz, Editorial Comment, American Journal of International Law, vol.41, p.878.

(28) L. Oppenheim, International Law, vol.2, ed. H. Lauterpacht, (London: Longmans, Green & Co.,1952), p.154.

(29) Stone, op. cit., p.14.

(30) Allan Gerson, “Trustee-Occupant: The Legal Status of Israel’s Presence in the West Bank,” The Harvard International Law Journal, vol.14, no.1, Winter 1973, p.17.

(31) United Nations, General Assembly, Document A/L. 519, 19 June 1967, paras.1, 3.

(32) United Nations, General Assembly, Official Records, 1535th Plenary Meeting, 26 June 1967, paras.1, 4. p.7 – subsequently circulated as Document A/L. 521.

(33) Ibid., 1548th Plenary Meeting, 4 July 1967, pp.15-17.

(34) Dershowitz, op. cit., pp.91-92.

(35) William V. O’Brien, “International Law and the Outbreak of War in the Middle East, 1967,” Orbis – A Quarterly Journal of World Affairs, vol. XI, no.3, Fall 1967, p.723.

(36) Blum, op. cit., p.294.

(37) Benjamin Halevi, Symposium on Human Rights, Israel Yearbook on Human Rights, vol.1, 1971, op. cit., p.369.

38) Levine, op. cit., p.495.(38)

(39) Stephen Schwebel, Symposium on Human Rights, op. cit., p.374.

(40) Stone, No Peace – No War in the Middle East, (Sydney: Maitland Publications, 1970), p.40.

(41) Blum, op. cit., pp.294-95 fn. 60.

(42) International Court of Justice, Reports of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders, 1953, The Minquiers and Ecrehos Case, Judgment of November 17th 1953, p.67.

(43) Joseph Nedava, Jordan is Arab Palestine, (The Institute for Israel Heritage, [n.d.]), p.8.

(44) League of Nations, Official Journal, 9th year, no.10, October 1928, Minutes of the Council, pp.1451-52.

(45) Treaty of London, dated 22 March 1946, Great Britain Foreign Office, Cmd. 6779.

(46) League of Nations, Official Journal, Special Supplement no.194, Records of the Twentieth (Conclusion) and Twenty-first Ordinary Sessions of the Assembly, Text of Debates at the Plenary Meetings of the Twenty-first Ordinary Session of the Assembly, Second Plenary Meeting, 9 April 1946 , p.28.

(47) Nedava, op. cit., p.13.

(48) United Nations, Security Council Official Records, Twenty-second year, Resolutions and Decisions of the Security Council 1967, Resolution 242 (1967) of 22 November 1967, pp.8-9.

(49) United Nations, Security Council Official Records, 1381st meeting, 20 November 1967, para.7.

(50) Ibid., para.9.

(51) United Nations, General Assembly, Document A/L. 519, 19 June 1967, para.2.

(52) United Nations, General Assembly, Official Records, 1535th Plenary Meeting, 26 June 1967, p.7, para.3 of draft resolution – subsequently circulated as document A/L. 521. (53) United Nations, General Assembly, Document A/L. 523/Rev.1, 4 July 1967, para.1(a).

(54) Ibid., Document A/L. 522/Rev. 3*, 3 July 1967, para.1.

(55) United Nations, General Assembly, Official Records, 1548th Plenary Meeting, 4 July 1967, pp.13-17.

(56) Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, vol.791, 17 November 1969, cols.844-45.

(57) “Brown ‘just as optimistic’,” Jerusalem Post, 20 January 1970, p.8. (58) Ibid.

(59) United Nations General Assembly Security Council, A/56/983, S/2002/669, 14 June 2002, Agenda Items 42 and 166, The situation in the Middle East. Measures to eliminate international terrorism. Letter dated 14 June 2002 from the Permanent Representative of Israel to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General.

(60) National Committee on American Foreign Policy, Security Interests, U.N. Resolution 242: Origin, Meaning, and Significance, April 2002 (Internet: www.mefacts.com/cache/html/arab-countries/10159.htm).

(61) Shabtai Rosenne, “On Multi-lingual Interpretation,” Israel Law Review, vol.6, 1971, p.362.

(62) United Nations, Security Council Official Records, Resolution 242 , op. cit., French text, para.1(i).

(63) Rosenne, op. cit., p.363.

(64) Alex Safian, “Backgrounder: Camp David 2000, Facts and Final Status Issues,” Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting in America – CAMERA, (Internet: www.camera.org/index.asp?x article=196&x context=2).

(65) International Court of Justice, Reports of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders, 1955, Voting Procedure on Questions relating to Reports and Petitions concerning the Territory of South-West Africa, Advisory Opinion of June 7th, 1955, p.72.

(66) Rosenne, op. cit., p.365.

(67) Arthur Lall, The UN and the Middle East Crisis, 1967, (New York: Colombia University Press, 1968), p.254.

(68) Rosenne, op. cit., p.364.

(69) Secure and Recognized Boundaries, (Jerusalem: Carta, 1974); The Meaning of “Secure Borders”, (Tel Aviv: Israelis Reply, [n.d.]).

(70) “Die Sackgasse ist Arabisch”, Die Spiegel, 5/1969, 27 January 1969, pp.86-88. The text in the original German says: “EBAN: Wir haben jedenfalls offen gesagt, daß die Landkarte niemals wieder so aussehen wird wie am 4. Juni 1967. Für uns ist das eine Sache der Sicherheit und von Prinzipien. Die Juni-Landkarte ist für uns gleichbedeutend mit Unsicherheit und Gefahr. Ich übertreibe nicht, wenn ich sage, daß sie für uns etwas von einer Auschwitz-Erinnerung hat. Denn wenn wir an unsere Situation im Juni 1967 denken und daran, was uns im Fall einer Niederlage erwartet hätte, dann überkommt uns ein Schaudern: die Situation mit den Syrern auf den Bergen und wir im Tal, mit der jordanischen Armee in Sichtweite der Küste, mit den Ägyptern, die in Gaza die Hand an unserer Kehle hatten. Das ist eine Situation, die in der Geschichte niemals wiederkehren wird.”

(71) Memorandum for the Secretary of Defense dated 29 June 1967, signed by Earle G. Wheeler, Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, on the subject of “Middle East Boundaries”, (JCSM 373-67).

(72) Richard Brody, “What the Joint Chiefs Saw as ‘Defensible Borders’,” Wall Street Journal, 9 March 1983.

(73) United Nations, Security Council, Document S/1264/Corr.1, Egyptian-Israeli General Armistice Agreement. Signed at Rhodes on 24 February 1949.

(74) United Nations, Security Council, Document S/1302/Rev.1, Hashemite Jordan Kingdom-Israel: General Armistice Agreement. Signed at Rhodes on 3 April 1949.

(75) United Nations, Security Council, Official Records, 1345th Meeting, 31 May 1967, para.84, p.9.

(76) Balfour Declaration: letter written by Lord Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary to Lord Rothschild on 2 November 1917. The original is in the British Museum. The text can be found in numerous books and is officially reproduced in Palestine Royal Commission Report, Cmd. 5479 (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1937), p.22.

(77) The Mandate for Syria and Lebanon was signed in London on 24 July 1922.

(78) League of Nations, Official Journal, 3rd year, no.8, August 1922, Annex 391a, French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, p.1013.

(79) Draft Mandates for Mesopotamia and Palestine, Miscellaneous no. 3 (1921), Cmd. 1176, (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1921), Draft Mandate for Mesopotamia, Article 1, p.2.

(80) Palestine Royal Commission Report, op. cit., p.39.

(81) Dan Bahat, ed., The Forgotten Generations, (Jerusalem: The Israel Economist, 1975), gives a survey century by century from the 1st to the 19th centuries of the Jewish presence in Palestine.

(82) e.g. in the weekday Amidah prayer –“and gather us from the four corners of the earth to our Land,” and in the Sabbath prayers – “lead us up in joy into our Land.”

(83) Shulchan Aruch Orach Chaim, chap.94 para.1.

(84) Palestine Royal Commission Report, op. cit., p.40.

(85) Emir Feisal was a son of Hussein, the Sherif of Mecca, and was later King of Iraq. Chaim Weizmann was the leader of the Zionist movement. A copy of the agreement can be found in The Israel-Arab Reader, ed. Walter Laqueur, (U.S.A.: Bantam Books, 1976), pp.18-20.

(86) Professor Felix Frankfurter was one of the leaders of U.S. Jewry and was later a Judge in the United States Supreme Court. A copy of the correspondence can be found in The Israel-Arab Reader, op. cit., pp.21-22.

(87) A copy of its recommendations can be found in The Israel-Arab Reader, op. cit., pp.23-31.

(88) Julius Stone, Self-Determination and the Palestinian Arabs, (Sydney: A Bridge Publication, December 1970), p.3.

(89) Harry Luke and Edward Keith-Roach, The Handbook of Palestine and Trans-jordan, (London: Macmillan, 1930), pp.38-40.

(90) Esco Foundation for Palestine, Palestine – a Study of Jewish, Arab, and British Policies, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1947), p.462.

(91) Martin Gilbert, The Jews of Arab Lands, (London: Board of Deputies of British Jews, 1976); The Hon. Terence Prittie and Bernard Dineen, The Double Exodus, (London: The Goodhart Press, [n.d.]), pp.20-25.

(92) Hearing before the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry, State Department building, Washington D.C., 11 January 1946 (Washington: Ward & Paul), p.10.

(93) Ibid., p.46.

(94) James Dorsey, “Wij zijn alleen Palestijn om politieke reden,” Trouw (Holland), 31 March 1977. The text in the original Dutch says: “Wij zijn een volk. Alleen maar om politieke redenen onderschrijven wij zorgvuldig onze Palestijnse identiteit. Het is namelijk van nationaal belang voor de Arableren om het bestaan van een aparte Palestijnen aan te moedigen tegenover het zionisme. Ja, het bestaan van een aparte Palestijnse identiteit is er alleen om tactische redenen. De stichting van een Palestijnse staat is een nieuw middel om de strijd tegen Israel en voor de Arabische eenheid voort te zetten.”

(95) Joseph Farah. “A Report on Arab America” a briefing, 18 May 2001, The Middle East Forum, (Internet: www.meforum.org/article/12).

(96) “The Palestine Report,” Advertisement – compiled by the Free Palestine Information Office, The Guardian (London), part 1, 14 May 1976, pp.11-18, part 2, 15 May 1976, pp.11-14.

(97) Encyclopedia Judaica, (Jerusalem: Keter, 1978), vol.13, col.29

(98) The information given in this section comes mainly from: Oded Avissar, ed., Sefer Hebron, 2nd edition, (Jerusalem: Keter, 1978), pp.27-65; Encyclopedia Judaica, op. cit., vol.8, cols.226-36; Jewish Virtual Library, Hebron, (Internet: www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/ History/hebron. html).

(99) Sefer Hebron, op. cit., p.30.

(100) Shelomo Alfassa of the International Sephardic Leadership Council, A Sephardic Perspective on Hebron, 20 January 2006, p.3, (Internet: www.sephardiccouncil.org/sph.pdf); Yehuda Novoselsky, Kiryat-Arba is Hebron, translation from Russian by Galina Tamarkin-Kotlyar, (Kiryat Arba, 2006), pp.10-11.

(101) List of all those buried in this cemetery appears on the Internet: www.pikholz.org/Hevron/Hevron.html

(102) Numerous photographs of the victims and the destruction left in the wake of the massacre are to be found in the book edited by Rachavam Ze’evi, Hebron Massacre 5689 [1929], (Jerusalem: Chavatzelet,1994).

(103) Sefer Hebron, op. cit, pp.396-99 - including a number of photographs; a photograph of the latrine built in the Jewish cemetery may be found in the article “The Cemeteries at Hebron,” The Times of Israel (Tel Aviv), 5 September 1969, p.7.

(104) Sefer Hebron, op. cit, pp.326-27; this incident was reported in the various Palestine newspapers of that period.

(105) Haaretz online, 11 January 2007 – from Israel Interior Ministry statistics.

(106) United Nations, Treaty Series, vol.75, 1950, no.973, Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War of August 12, 1949.

(107) Julius Stone, Israel and Palestine, (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1981), pp.177-78.

(108) Conference of High Contracting Parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention, Geneva, 15 July 1999, Statement.

(109) United Nations, General Assembly, Official Records, 71st Plenary session, 6 December 1999, Resolution 54-77, pp.20-21.

(110) Unfortunately politics and self-interest override justice in many of the decisions of the United Nations. Because of Arab oil power and other factors, there have been a completely disproportionate number of condemnations of Israel. It was Abba Eban who said “you could have a resolution at the United Nations saying that the Earth is flat, and if it were put forward by an Arab country, it would automatically get 70 or more votes.” (Minutes of U.S. House of Representatives, 9 July 2004). If therefore an anti-Israel resolution is defeated, (such as those proposed by the Soviet Union and by Albania after the Six Day War to condemn Israel for her “aggression” during this war), one can be sure that Israel’s case is very strong indeed!

(111) Quincy Wright, “Legal Aspects of the Middle East Situation,” Law and Contemporary Problems, vol.33, no.1, Winter 1968, The Middle East Crisis: Test of International Law, p.18.

(112) International Committee of the Red Cross, Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, Geneva, 12 August 1949, Commentary.

(113) Ibid., Article 49 – Deportations, Transfers, Evacuations, paragraph 6, Deportations and Transfer of Persons into Occupied Territory, p.283.

(114) Encyclopedia Judaica, op. cit., vol.8, col.235; Novoselsky, op. cit., pp.19-20.

(115) Novoselsky, op. cit., p.23; “Beit Hadassah and Beit HaShisha,” Website of The Jewish Community of Hebron, 9 April 2006, (Internet: www.hebron.com/english/article.php?id=227).

(116) International Court of Justice, Reports of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders, 2004, Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion of 9 July 2004, para.120, p.183.

(117) The evictions were from a Jewish owned building in the Casbah, from buildings on Jewish-owned land just in front of the “Avraham Avinu” complex and from a building renamed “Beit Shapira” which had been rented from the Arabs.